Anne Spencer

Anne Spencer was born Anne Bethel Scales Bannister on February 6, 1882, on a plantation in Henry County, Virginia, to former slaves, Joel Cephus Bannister and Sarah Louise Scales, the daughter of a slaveholder. Spencer’s parents separated in the late 1880s. Her mother supported the family by working as an itinerant cook. Financial hardship led to Spencer being temporarily placed with a foster family in Bramwell, West Virginia, though she was still cared for by her mother, who was determined to raise Spencer as member of the black bourgeoisie. When she was eleven, Spencer began studying at Virginia Theological Seminary and College (now, Virginia University of Lynchburg) in Lynchburg, Virginia. She graduated at seventeen as valedictorian.

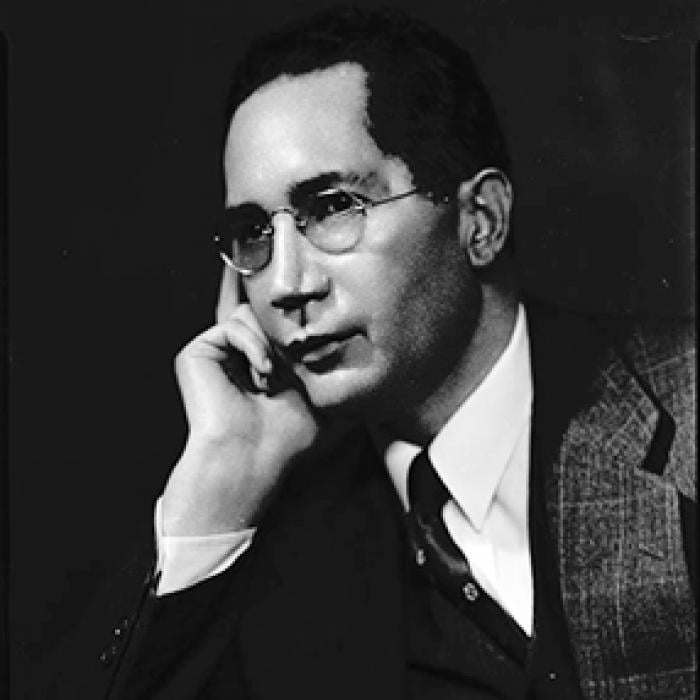

Spencer remained in Lynchburg for most of her adult life. She married fellow Virginia Seminary student, Edward Alexander Spencer, and had three children. Spencer then opened and managed the library at Dunbar High School. While establishing a chapter of the NAACP in Lynchburg, she met James Weldon Johnson, then field secretary of the NAACP.

Spencer published more than thirty poems in anthologies, including Johnson’s seminal work, The Book of American Negro Poetry (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1922); Countee Cullen’s Caroling Dusk (Harper & Brothers, 1927); and Alain Locke’s The New Negro, as well as in Opportunity and Crisis magazines. Spencer never released a poetry volume during her lifetime, as she was often frustrated by editors and publishers who censored or misunderstood her work. Spencer was the second African American and the first African American woman whose work was published in the Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry (W. W. Norton, 1973). Her work was also published posthumously in Time’s Unfading Garden: Anne Spencer’s Life and Poetry (Louisiana State University, 1977) by J. Lee Greene, a book that is now out of print.

Spencer hosted a literary salon during the Great Depression and World War II in the Queen Anne-style home her husband designed and built. Her guests included W. E. B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, and Langston Hughes. Spencer was also a botanist. She became a controversial figure within the African American community in the mid-century, due to her preference for wearing pants and her aversion toward school integration. Meanwhile, she also offended whites with her diatribes against both white supremacy and interracial friendships. Spencer once offered her home as a refuge to Ota Benga, the Congolese man who was kidnapped, kept in a cage, and exhibited at the St. Louis World’s Fair (formally known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition) in 1904.

Spencer, who died on July 27, 1975, in Lynchburg, left behind unpublished work, including a novel and cantos in honor of abolitionist John Brown.