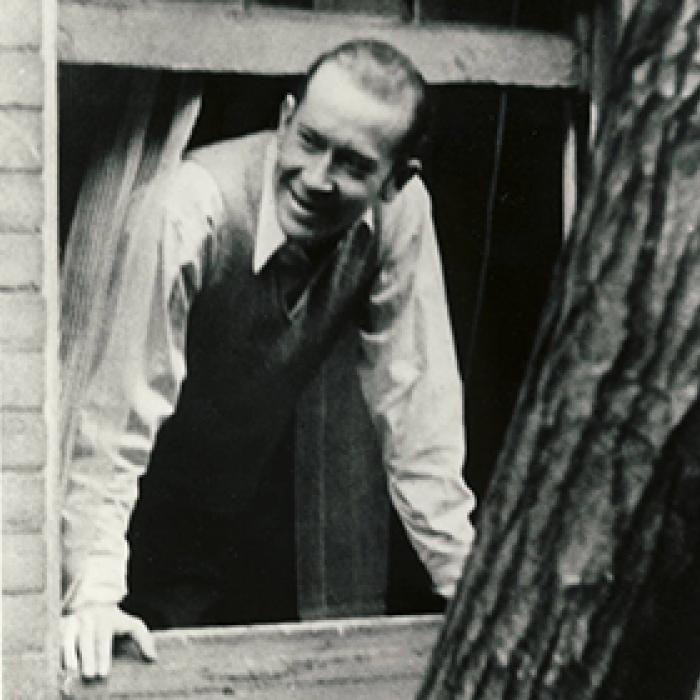

Edward Thomas

On March 3, 1878, Philip Edward Thomas was born in Lambeth, London, the eldest of six sons of Welsh parents. As a child, Thomas spent many holidays in both Wales and Wiltshire, where he explored the landscape of Richard Jefferies, his first literary hero. Thomas was educated at several schools, including Battersea Grammar School and St. Paul's School in London. His father, who worked as a civil servant, wanted Thomas to enter the same field and urged his son to study for the civil service examination after leaving St. Paul's in 1895. Though he acquiesced and prepared for the exam, Thomas retained his desire to write and began publishing essays instead of pursuing a career in the civil service.

Encouraged by critic James Ashcroft Noble, Thomas compiled and published his first book, The Woodland Life in 1896, a collection of essays about his long walks. Thomas began a relationship with Noble’s second daughter, Helen Berenice Noble. They married in 1899, while she was pregnant with their son, Merfyn. Shortly after their first child was born, Thomas won a scholarship to Lincoln College in Oxford and later graduated with a degree in history, further diverging from the career path his father hoped he would follow.

For many years, Thomas supported his family through a series of reviewing positions. He succeeded Lionel Johnson as a regular reviewer for the Daily Chronicle, reviewing contemporary poetry, reprints, criticism, and country books, but was earning less than 2 pounds a week, forcing him to sacrifice creative writing for more necessary work. The Thomases moved five times in a ten year span, during which their two daughters were born, Myfanwy in 1910, and Bronwen in 1913. Most notably, in 1906, they moved to Petersfield in Hampshire, and later to the nearby Yew Tree Cottage in Steep, where the countryside had an immediate influence on Thomas’s poetic landscapes.

During this time, Thomas published a number of important critical and biographical studies, including Richard Jefferies (1909), Maurice Maeterlinck (1911), Algernon Charles Swinburne (1912), and Walter Pater (1913). Unsatisfied by work which he felt repressed his creativity, and under the constant stress of financial strains, Thomas endured poor health and recurrent physical and psychological breakdowns. His unhappiness was a great strain on his marriage, as were a few platonic friendships with women, such as the writer, Eleanor Farjeon. However, Thomas's well-being improved significantly following the family's move to Steep Village in 1913, where he began writing more creative and often autobiographical work. He began work on Childhood, and wrote The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans (1913), The Icknield Way (1913), and In Pursuit of Spring (1914).

At this same time, the poet Robert Frost and his family moved into a nearby cottage. Frost was just at the start of his career, and the two men developed a strong friendship, taking long walks in the countryside together and gathering with a lively community of local writers in the evenings. Later, Frost wrote of their time together: "I never had, I never shall have another such year of friendship." It was during this precarious time, as World War I began, that Frost persuaded Thomas to begin writing poetry. He wrote his first real poem in 1914, the blank-verse dialogue "Up in the Wind," which was published, along with much of his later work, under the pseudonym Edward Eastaway. Thomas himself helped build Frost's reputation by writing a rave review of North of Boston in 1914.

As the literary market collapsed during the war, Thomas found more time to write poetry. He struggled with the difficult choice between moving with his family to New England, as Frost urged, or enlisting as a soldier. In July 1915, he joined the Artists' Rifles and was sent in November to Hare Hall Camp in Romford, Essex. He became a Lance Corporal and instructed his fellow officers, including the poet Wilfred Owen. While at Hare Hall Camp for ten months, Thomas wrote over 40 poems; in just two years, he wrote over 140 poems.

Written during wartime, while serving as a soldier, much of Thomas's work blends and shifts between meditative recollections of his beloved countryside and his experiences in battle. In a review in The Guardian, Ian Sansom writes: "If anything explains the continuing appeal of his poems, it's probably that Thomas seems to have no clear idea of what he's doing or where's he's going; the effort is all. Many of the poems feature a first-person narrator who is tramping along, overlooked by others, a visitor in the landscape, passing by beguiling streams and fields, often in the rain, listening to much thrush-song and 'parleying starlings' and 'speculating rooks', and getting absolutely nowhere. Happiness, life and love all lie just out of reach—a leap, or a walking-stick's length away."

In September of 1916, Thomas began training as an Officer Cadet with the Royal Garrison Artillery, and by November he was commissioned Second Lieutenant. He volunteered for service overseas and was sent to northern France, where he was stationed at Le Havre, Mondicourt, Dainville, and finally at Arras. On the first day of the battle at Arras, April 9, 1917, Thomas was killed by a shell blast. He was buried the following day in Agny military cemetery.