While poets may not always experience the most poetic of deaths, many mark their final moments with the most lyrical, memorable, funny—and occasionally mysterious—last words. Check out this list of famous last lines from historic poets and the strange, sad, and interesting tales that accompany them.

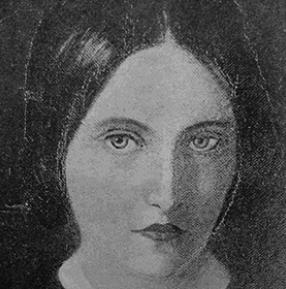

Charlotte Brontë: “Oh, I am not going to die, am I? He will not separate us. We have been so happy.”

Charlotte Brontë: “Oh, I am not going to die, am I? He will not separate us. We have been so happy.”

On June 29, 1854, Charlotte Brontë wed Arthur Bell Nicholls in Haworth, England, and enjoyed a month-long honeymoon in Ireland. Once the couple returned home in August, Brontë was in high spirits and good health, writing to a friend, “It is long since I have known such comparative immunity from headache, sickness, and indigestion as during the past three months.” However, that soon changed in January 1855, when she wrote that her “stomach seemed quite suddenly to lose its tone, indigestion and continual faint sickness has been my portion ever since.” Soon Brontë was suffering from constant nausea, vomiting, and faintness, which her physician attributed to a “natural cause” that would pass, such as morning sickness. But Brontë’s symptoms only became worse; she became emaciated and spent more and more time in bed. In mid-February, Brontë made her will, and most of her remaining time was spent in a state of delirium. In one lucid moment, however, in the early morning of March 31, 1855, while her husband was praying for her life, she declared, “Oh, I am not going to die, am I? He will not separate us. We have been so happy.” But Brontë died that day, just nine months after her wedding and three weeks before her thirty-ninth birthday.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning: “Beautiful.”

Elizabeth Barrett Browning: “Beautiful.”

In 1860, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning discovered that Barrett Browning’s sister had died. Barrett Browning was dramatically affected by the news, which led her into bouts of depression. She gradually became weaker until she died on June 29, 1861, in Browning’s arms. In an account of his wife’s death, Browning wrote that she died “smilingly, happily, and with a face like a girl’s. … Her last word was— … ‘Beautiful.’” Barrett Browning’s actual cause of death is still unclear, but scholars have speculated that her history of pulmonary problems, combined with opiates she was taking at the time, may have contributed to her death.

Robert Browning: “How gratifying!”

Robert Browning: “How gratifying!”

Just before his death, Robert Browning was preparing for the publication of his newest collection, Asolando, and was enjoying some time in Venice, giving readings of his new poems and attending social events with friends. In late November 1889, he caught a cold while on a walk but refused to stay home from his social engagements and refused to see a doctor (“They are all fools,” he claimed). Eventually Browning’s conditioned worsened to such an extent that a doctor was brought in, who diagnosed the poet with bronchitis and “syncope of the heart,” or an irregular heartbeat. On December 12, despite his ongoing symptoms, Browning was cheered up by his receipt of his author’s copy of Asolando, saying with admiration, “What a pretty color the binding is.” That evening, when he asked if there was any news about how the new collection was received, his son read him a telegram from the publisher: “Reviews in all this day’s papers most favorable. Edition nearly exhausted.” Browning smiled and muttered, “How gratifying!” before passing away.

Robert Burns: “Don’t let the awkward squad fire over my head!”

Robert Burns: “Don’t let the awkward squad fire over my head!”

Though there is much speculation and disagreement about the exact cause of Robert Burns’s death, what is known is the fact that the poet exhibited good humor and wit, even as he faced the end of his life. When his doctor visited him, Burns said, “Alas! What has brought you here? I am but a poor crow and not worth plucking.” And when Burns saw a fellow member of the Royal Dumfries Volunteers standing teary-eyed at his bedside, Burns proclaimed, “John, don’t let the awkward squad fire over me!” Poet and biographer Allan Cunningham reports that Burns then reassured his friends that he had lived long enough. Over the course of the next few days, Burns’s fever worsened, his strength diminished, and he was reduced to a state of delirium. He died on July 21, 1796.

Lord Byron: “Come, come, no weakness! Let’s be a man to the last!”/“Now, I shall go to sleep.”

Lord Byron: “Come, come, no weakness! Let’s be a man to the last!”/“Now, I shall go to sleep.”

There is some debate over the last words of Lord Byron, but the circumstances around his death in both versions remain the same. When he was a boy, a famous fortune-teller in Scotland told Byron he should beware of his thirty-seventh year. That year the poet found himself in Greece, where he fell ill. Unfortunately, he was attended to by two young, inexperienced doctors who repeatedly drew his blood in an attempt to heal his illness—a common practice in that day. Byron clearly had forebodings of death and initially resisted the treatments, calling the doctors a “damned set of butchers,” but he allegedly rallied at the last moment, declaring, “Come, come, no weakness! Let’s be a man to the last!” In The Life, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron, Thomas Moore writes the following account of Byron’s death: “It was about six o’clock in the evening of this day when he said, ‘Now I shall go to sleep’; and then turning round fell into that slumber from which he never awoke. For the next twenty-four hours he lay incapable of either sense or motion—with the exception of, now and then, slight symptoms of suffocation, during which his servant raised his head—and at a quarter past six o’clock on the following day, the 19th, he was seen to open his eyes and immediately shut them again. The physicians felt his pulse—he was no more!” Byron died on April 19, 1824.

Lewis Carroll: “Take away those pillows. I shall need them no more.”

Lewis Carroll: “Take away those pillows. I shall need them no more.”

At age sixty-five, Carroll was strong and in good health; in 1897, after undertaking a twenty-mile walk between Eastbourne and Hastings, he said, “I was hardly at all tired and not at all foot sore.” During Christmas of that year, he came down with what he described in a letter to his sister as a “feverish cold, of the bronchial type” that eventually worsened and turned into pneumonia. Though pneumonia was often fatal at that time, Carroll did not fear death; in fact, he once wrote in an 1896 letter to his sisters, “I sometimes think what a grand thing it will be to be able to say to oneself, ‘Death is over now; there is not that experience to be faced again.’” It is with this attitude that Carroll calmly faced his death in the end, in January 1898, as his sisters sat with him in bed, propping him up on pillows to help him breathe. On January 13, Carroll told them, “Take away those pillows. I shall need them no more,” and he died on the next day.

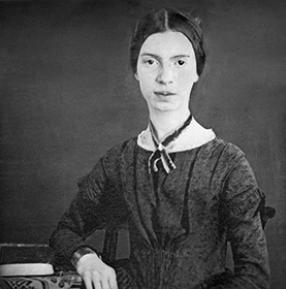

Emily Dickinson: “I must go in; the fog is rising.”

Emily Dickinson: “I must go in; the fog is rising.”

“Because I could not stop for Death - / He kindly stopped for me” writes Emily Dickinson in one of her many, famous poems about death, time, and loss. Dickinson herself encountered death many times over the course of her life, as she endured the loss of several friends (Charles Wadsworth, Judge Otis P. Lord, and Helen Hunt Jackson) and family members (her nephew Gib and her mother) over the course of a decade. Dickinson’s health declined drastically during this time as well, as she became what her sister called “delicate” and became confined to her bed. In her last days she was only able to write short notes, and her “briefest last message,” according to her niece, Martha, contained the ominous and poetic last words: “I must go in; the fog is rising.” There was some precedence, however, for the use of this phrase in the Dickinson household; it was reminiscent of an oft-repeated family caution: “It was already growing damp.” Dickinson died on May 15, 1886, to what was diagnosed as “Bright’s Disease,” but more contemporary researchers have concluded that she died of heart failure caused by severe hypertension.

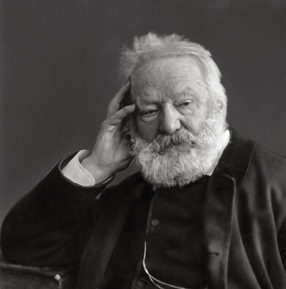

Victor Hugo: “Here is the battle of day against night. I see black light.”

Victor Hugo: “Here is the battle of day against night. I see black light.”

Shortly before his death, Victor Hugo had a stroke, and four days later, on his deathbed, while afflicted with pneumonia, Hugo said, “Here is the battle of day against night.” As he died, he whispered, “I see black light.” Hugo died on May 22, 1885, and his funeral was a national event; hundreds of thousands of people, including representatives of many other European countries, attended the ceremony and followed the funeral procession through Paris.

James Joyce: “Does nobody understand?”

James Joyce: “Does nobody understand?”

As Joyce is known as one of the most challenging writers in the English language, particularly for his associative, stream-of-consciousness novels Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, it’s perhaps fitting then that his alleged last words address a failure of comprehension: “Does nobody understand?” Joyce died on January 13, 1941, in Zurich of a perforated duodenal ulcer, at the age of fifty-nine.

John Keats: “I can feel the daisies growing over me.”

John Keats: “I can feel the daisies growing over me.”

In 1818, John Keats returned home from a tour of Northern England and Scotland to care for his brother, who had contracted tuberculosis. Unfortunately, Keats’s brother died in December of that year and by that time Keats himself had contracted the disease and knew that his death was imminent. Following his doctor’s orders to seek a warm climate for the winter, Keats traveled to Rome with his friend, the painter Joseph Severn. Keats recovered briefly for Christmas but on January 10, 1819, his health took a final turn for the worst and Keats was unable to leave his bedroom. Just before Keats’s death, Severn asked the poet how he was doing, to which Keats quietly replied, “Better, my friend. I feel the daisies growing over me.” Keats died in Severn’s arms on February 23, 1821, at the age of twenty-five.

Philip Larkin: “I am going to the inevitable.”

Philip Larkin: “I am going to the inevitable.”

This bleak goodbye was spoken by a somber Philip Larkin at the time of his death. Larkin, who had trouble writing near the end of his life, did not publish anything of acclaim in his final eight years—nothing since “Aubade” in 1977. Larkin came to feel as though all poetry had left him. Wracked with declining health and deepening depression, along with the fear that he would die at age sixty-three (the same age at which his father had passed away), Larkin died of cancer in December 1985—indeed, at the age of sixty-three. His last words, he said, in fear, to an attending nurse in the middle of the night: “I am going to the inevitable.”

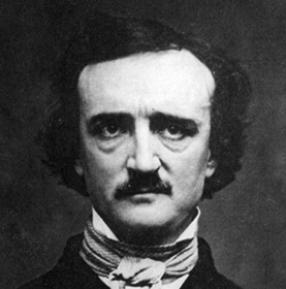

Edgar Allan Poe: “Lord, help my poor soul.”

Edgar Allan Poe: “Lord, help my poor soul.”

No stranger to the mysterious and macabre, Edgar Allan Poe died amidst peculiar circumstances. On October 3, 1849, Poe was found semiconscious in Baltimore wandering around in cheap, ill-fitting clothing—so ill-fitting and unusually contrasted against Poe’s usual mode of dress, in fact, that many believed Poe’s own clothes had been stolen. Poe had left Richmond a week earlier, intending to arrive in Philadelphia; how he arrived in Baltimore was a mystery. Poe was taken to Washington College Hospital, where he spent days in varying states of delirium and unconsciousness until, on his fourth night at the hospital, he started calling loudly for a “Reynolds”—a figure who still remains a mystery. On the morning of October 7, Poe uttered his last words, “Lord, help my poor soul” and died from what was determined to be “congestion of the brain.” However, no autopsy was performed, and Poe was buried two days later.

Alexander Pope: “Here am I, dying of a hundred good symptoms.”

Alexander Pope: “Here am I, dying of a hundred good symptoms.”

As Alexander Pope was best known for his writing on religion and morality, such as his Essay on Man, it is perhaps no surprise that shortly before his death, he sent out several copies of his Ethnic Epistles as presents to his friends. With his characteristic wit, Pope joked about these presents, saying, “I am like Socrates, distributing my morality among my friends just as I am dying.” It was this same humor that he drew on in the end, as he spoke to his doctor on the morning of his death; the doctor, examining him, noted that his pulse was good and made other positive comments on Pope’s condition, to which Pope calmly responded: “Here am I, dying of a hundred good symptoms.” Pope died calmly and quietly, surrounded by friends, on May 30, 1744.

Christina Rossetti: “I love everybody. If ever I had an enemy, I should hope to meet and welcome that enemy to heaven.”

Christina Rossetti: “I love everybody. If ever I had an enemy, I should hope to meet and welcome that enemy to heaven.”

One of the things Christina Rossetti was noted for both in her poetry and in her life was her attention to matters of religious faith. The women in her family were dedicated High Church Anglicans, and when Rossetti suffered a nervous breakdown as a teenager, it was diagnosed as “religious mania.” Religious themes dominated in Rossetti’s work, which also consisted of devotional prose. Later in life, however, Rossetti suffered from Graves’ disease, a thyroid disorder, which limited her mobility, and was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1892. But despite her illness, Rossetti’s warm outlook, undoubtedly informed by her religious faith, led her to these last words before she died in London on December 29, 1894, elicit a sense of hope and contentedness: “I love everybody. If ever I had an enemy, I should hope to meet and welcome that enemy to heaven.”

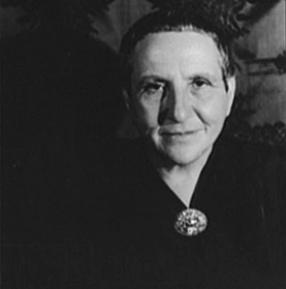

Gertrude Stein: “What is the answer? … In that case, what is the question?”

Gertrude Stein: “What is the answer? … In that case, what is the question?”

In the 1940s, Gertrude Stein was diagnosed with advanced stomach cancer, and her last exchange with her partner, Alice B. Toklas, was notable. While in a hospital in Neuilly, France, Stein regained consciousness for just a few minutes following surgery, during which she asked, “What is the answer?” When she received no answer, she said, “In that case, what is the question?” before falling into a coma. Stein died later that day, on July 19, 1946.

Robert Louis Stevenson: “What’s that? Do I look strange?”

Robert Louis Stevenson: “What’s that? Do I look strange?”

On the day of his death, December 3, 1894, Robert Louis Stevenson had worked all morning on his half-finished book, Hermiston, and wrote long letters to friends before joining his wife downstairs to prepare for dinner. Though his wife had a foreboding feeling about his health, Stevenson dismissed this, talking about his plans to go on a lecturing tour to America “as he was now so well.” Then, according to an account by his stepson, Lloyd Osbourne, “He was helping his wife on the verandah, and gaily talking, when suddenly he put both hands to his head, and cried out, ‘What’s that?’ Then he asked quickly, ‘Do I look strange?’ Even as he did so he fell on his knees beside her.” Stevenson died later that day, at the age of forty-four, from a stroke.

Dylan Thomas: “I’ve had eighteen straight whiskies—I think that’s the record.”

Dylan Thomas: “I’ve had eighteen straight whiskies—I think that’s the record.”

According to legend, Dylan Thomas drank himself to death in New York City on November 9, 1953, after a superhuman binge-drinking session that ended at the famous White Horse Tavern. While Thomas’s cause of death has been widely attributed to alcohol poisoning, scholars have argued that that is just a misconception, and that the main cause of death was pneumonia and medical neglect. The poet’s record-breaking binge is also likely conjecture or exaggeration, as several sources claimed he had nowhere near the eighteen whiskies he is said to have drunken.

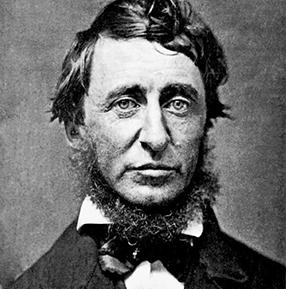

Henry David Thoreau: “Moose … Indian.”

Henry David Thoreau: “Moose … Indian.”

Though Thoreau was known for his good diet and healthy lifestyle of moderation, unfortunately, at the age of forty-four, the writer still succumbed to tuberculosis, which was endemic to his family. Still, Thoreau’s last words were fitting for a man who wrote about finding harmony with the natural world and admired the lifestyle of Native Americans: “Moose … Indian.”

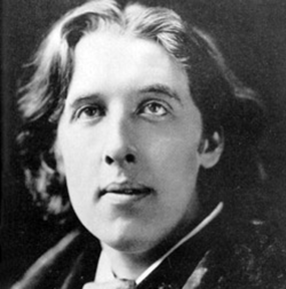

Oscar Wilde: “My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or the other of us has to go.”

Oscar Wilde: “My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or the other of us has to go.”

Though these words, spoken by Oscar Wilde on his deathbed in Room 16 of the Hôtel d’Alscade in Paris, are famously attributed as the poet’s last words, the truth is that Wilde didn’t actually die until weeks later. Still, literary lore has generally adopted these words as Wilde’s last, a fitting farewell from a writer known for his wit and flair. But this was not the first time Wilde took offense to interior decorating. “Modern wallpaper is so bad,” he once said in a lecture, “that a boy brought up under its influence could allege it as a justification for turning to a life of crime.” During a visit to America, the writer was asked why he thought American society was so violent, to which he replied, “Because your wallpaper is so ugly.” Wilde died on November 30, 1900. Wilde himself, before his death, claimed to have suffered from syphilis—a claim never confirmed—and some contemporary scholars believe the writer died from a spreading ear infection.