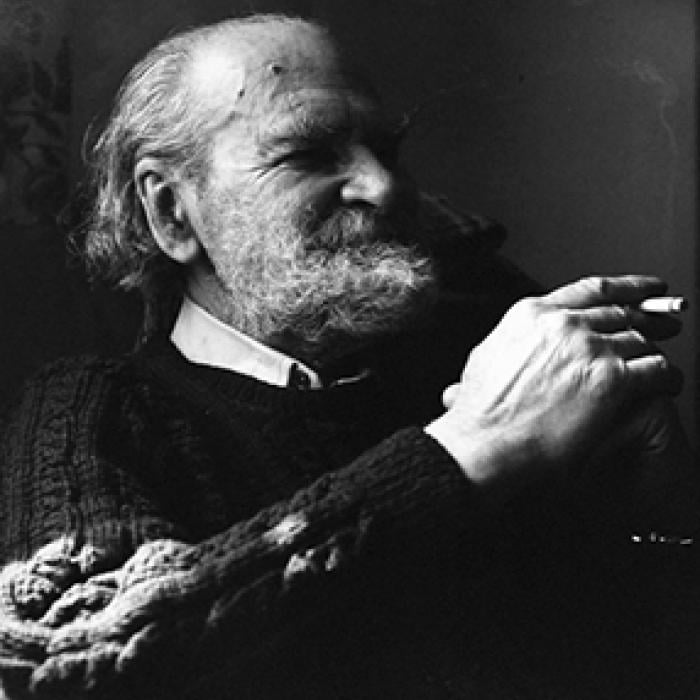

Louis Zukofsky

Born on January 23, 1904, Louis Zukofsky grew up in New York City’s Lower East Side to Orthodox Jewish immigrants from what is now Lithuania. The only one of his siblings born in the U.S., Zukofsky grew up in a Yiddish-speaking family and community. His first encounter with literature was Yiddish adaptations of Shakespeare, Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg, and Leo Tolstoy at the local theaters. He first read Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Hiawatha and Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound in Yiddish, though by age eleven he had read all of Shakespeare in English.

Although Zukofsky’s family was poor, and though he could have gone to City College for free, his parents sacrificed and sent him to Columbia University, where he studied both English and philosophy. In 1924 he received his master’s degree in English, having studied with prominent scholars such as poet Mark Van Doren, philosopher John Dewey, and novelist John Erskine.

While in school, Zukofsky singled out Ezra Pound as the only living poet that mattered, just as Pound had done years earlier with William Butler Yeats. In 1927, Zukofsky sent Pound his “Poem beginning ‘The,’” a slanted parody of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land that addresses the poet’s mother and includes slices of Dante and Virginia Woolf. Pound was impressed by the poem and published it a year later in the journal Exile. Zukofsky further impressed Pound by writing the first analyses of Pound’s The Cantos in 1929, which were still unfinished at the time. Pound then persuaded Harriet Monroe, Chicago heiress and founder of Poetry, to allow Zukofsky to edit a special issue for her in February of 1931.

Zukofsky’s special issue, “‘Objectivists’ 1931,” unveiled what would later become the Objectivist movement, a group of poets that included Charles Reznikoff, George Oppen, and Carl Rakosi, as well as Zukofsky himself. The issue also included work by poets who would remain associated with the group in various ways, such as William Carlos Williams and Kenneth Rexroth.

In 1932, Zukofsky edited An “Objectivists” Anthology (To Publishers, 1932), which further defined the group, though without indicating any single aesthetic position. Zukofsky’s own contribution to the anthology included the first seven movements of “A,” an ambitious poem in a juxtapositional style akin to that of The Cantos in its cohesiveness and length. Begun in 1927, Zukofsky spent the rest of his life working on “A,” expanding the epic to twenty-four sections, mirroring the hours of the day. The poem weaves together politics and family, traditional forms, and free verse, and features Zukofsky’s own father as a major theme. The complete version of “A” was finally at the printers when the poet died in 1978.

The 1930s proved to be an extremely busy decade for Zukofsky, in both his artistic and personal life. Not only did he continue to work on “A,” but he made great progress on a number of other manuscripts, including many short poems that were later collected in 55 Poems (The Press of James A. Decker, 1941), as well as the compilation A Test of Poetry (1948), a self-published teaching anthology. In 1933 he met musician and composer Celia Thaew, whom he courted and later married in August 1939. Their only son, Paul, was born in 1943. He was a child prodigy on the violin and eventually became one of the world’s most noted performers and conductors of twentieth-century music. Zukofsky’s family, specifically his wife, played a large role in his writing throughout his life, collaborating and offering key support for works such as his translation of Catullus (1969), his Autobiography (Grossman Publishers, 1970), and even sections of “A.”

Despite the attention Objectivism received as a major poetic movement of the 1930s, Zukofsky’s own work never achieved much recognition outside literary circles. His poetry tended to be obscure, experimental, and intellectual. As Guy Davenport wrote in the journal Parnassus, Zukofsky is a “poet’s poet’s poet,” one whose work is intended for a select audience of connoisseurs. In later years, Zukofsky’s work became deeply influential to poets in both the Black Mountain and Language movements.

When Zukofsky died on May 12, 1978, in Port Jefferson, New York, he had published forty-nine books, including poetry, short fiction, and critical essays. He had also won National Endowment for the Arts grants in 1967 and 1968, the National Institute of Arts and Letters grants in 1976, and an honorary doctorate from Bard College in 1977. The first complete edition of his work “A” (New Directions) and another collection, 80 Flowers (Stinehour Press), were published posthumously in 1978.