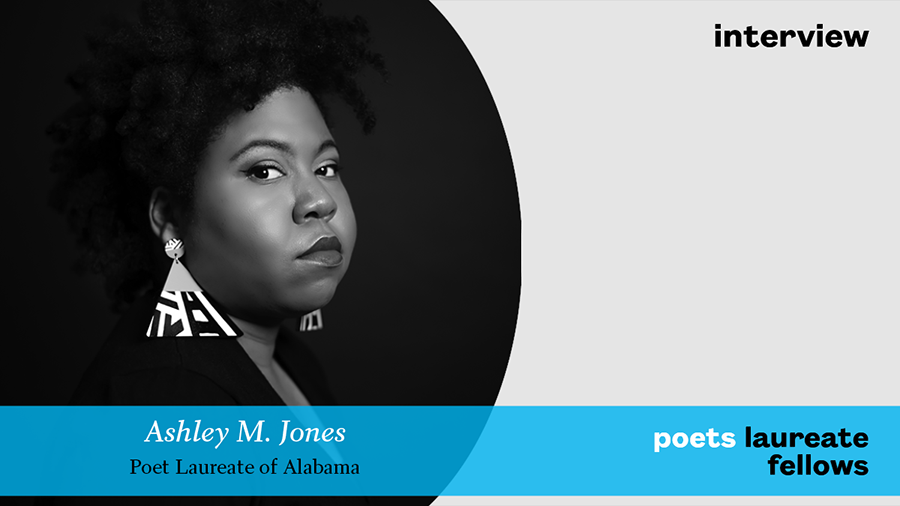

Ashley M. Jones is the author of several books, including REPARATIONS NOW! (Hub City Press, 2021), which was longlisted for the PEN/Voelker Award for Poetry and dark//thing (Pleaides Press, 2019), winner of the Lena-Miles Wever Todd Poetry Prize. She co-directs PEN Birmingham, and she is a faculty member in the creative writing department at the Alabama School of Fine Arts. In 2022, she received an Academy of American Poets Laureate Fellowship. Jones will implement the Alabama Poetry Delegation, a multi-regional leadership and service initiative which seeks to engage and support poetry projects and poets across the state. Jones will identify five regions and five regional delegates to shepherd poetry projects over three years.

Poets.org: What do you hope for the future of poetry in Alabama, and what support do you hope future poets laureate in the state have?

Ashley M. Jones: I have so much hope for the future of Alabama poetry—this community is so supportive, so vibrant and so varied; and I know we’re going to keep doing what people think we can’t do. I truly believe Alabama is a literary destination. We matter in the history of writing, and we’ll matter in the future, too. I hope Alabama poets never stop putting themselves out there. I hope we never believe that, because we’re from the Deep South, because we’re not New York, Chicago, L.A., or even Atlanta, that makes us less talented and less high-achieving. Poets from and in Alabama are doing big things.

I hope future poets laureate in Alabama receive the kind of community support and outpouring of love that I have received so far in my tenure. I have been overwhelmed and overjoyed by the way my state has rallied behind me and celebrated my work and my mission. It means everything that people wanted me to represent them. It means everything that people are happy to welcome me to their schools, bookstores, events, journals, and Zooms. My work is, largely, political, and it means so much to me to know that people are willing to hear what I have to say and listen to the heartbeat in it. Even if they don’t agree at the beginning of our interaction, they see my heart in my work and we can begin a conversation there—from our hearts. I hope every future poet laureate of Alabama experiences that. And I hope we continue to be supported by important national and international literary organizations, like the Academy of American Poets. This support has been so transformational in expanding my impact and reach as Alabama’s poet laureate. I am proud to represent my state on this stage and to highlight why we’re so worthy of resources and respect.

Poets.org: How has being a poet laureate changed your relationship to your own writing?

AMJ: People have asked me this a lot during my second year as poet laureate. I think the most interesting change in my relationship to my writing is that now I’m pursuing my own work in a way I haven’t had to before. That is, as poet laureate, I’m asked to write for many occasions. The challenge has been to keep making space for my own intentions and for deep listening, which is a crucial part of my process, to the Spirit that guides me. To God. For me, writing is a spiritual practice—a Holy gift. It is important to me that I’m always getting out of the way so the poetry can speak clearly, and so I can receive the gift of each word. Another way to think about this is to say, I don’t want to value my own ego more than I value the work and what it wants or needs to do. I have always written out of a need to understand and communicate. So, even when I’m asked to write for a specific reason or under particular constraints, I want to leave room for that authentic conversation to happen. I want each poem, regardless of its start, to be “real” and not transactional. I hope that’s making sense. And it is a challenge—deadlines and the pressure of expectations sometimes get to me, but when I feel that, I’ve tried to just let go of all the noise and just listen and record what I hear.

Poets.org: How can a poet, or poetry, bring a community together?

AMJ: I think poetry is a beautiful community-maker. The poet is a servant of the poetry, so when we’re in service of the work, we can also help strengthen and create community. I’ve found, in my life, that there’s something really inimitable about the way in which poetry can allow people (the poet included) to hear, find, or affirm their voices and remind them that we’re all here together as humans on earth. Our experiences are different, and that difference is beautiful, but we are also all here trying to make our way through life. Poems illuminate those lives and explore the human condition, and when we start to learn that we’re all bonded by that condition, community starts to form. For example, last week, we began the festival my nonprofit runs: the Magic City Poetry Festival. Our opening event, Poetry in the Park and a commemoration of the sixtieth anniversary of the Palm Sunday March, brought many different people together. Civil Rights foot soldiers, children, young adults, actors, singers, poets, clergy members—so many different kinds of Alabamians were in attendance. On the poetry walking tour, we heard from three very different poets who express themselves in very different ways. One stop, in front of the historic A.G. Gaston Motel, featured activist and poet Dikerius Blevins, who wrote “A Letter from a Hoover Jail” about his activism during 2020 in both Hoover and Birmingham, Alabama. Although we weren’t all the same age, or maybe even a part of the same political party, or even on the same side of the central demands of the freedom fighters who demonstrated in 2020, we all quieted to listen to Dikerius’s poem. We heard his human experience and it spoke to us. No one fanned the Alabama heat away. No one rolled their eyes or shouted back at him. We listened. We saw him clearly and connected to his unique and compelling story. People thanked him after his reading, and I know many of us felt gratitude for his vulnerability in the poem and for his dedication to his community. It is inspiring, and it bonds us. Poetry can create a new space that we can enter with mutual respect, curiosity, and empathy.

Poets.org: What part of your project were you most excited about?

AMJ: It’s hard to say because I’m so excited about everything! But I think I’d have to say I was very excited to share resources with the poets of Alabama and create an opportunity for people to address the needs of their communities without someone prescribing what those needs were. It has been so amazing, selecting the delegates and learning more about their projects, which will impact so many people in our state! I am passionate about making sure I do my part to open doors and keep them open. Or, in some cases, to knock the door frame down completely. Hierarchies and barriers are a tool of oppression, and I’m not interested in that. I’m from Alabama, and we are, despite popular belief, the birthplace of many revolutions. This is one—to empower poets from across the state to serve their neighbors by creating the programming they desire. I’m so thrilled to have been able to mobilize this work.

Poets.org: What obstacles, if any, did you experience when starting your project?

AMJ: I have to say that things have been remarkably smooth.I mean, yes, it always takes effort to spread the word and make sure your plan is logical, but the community has been receptive, and the delegates have been enthusiastic and industrious so far. Perhaps my biggest obstacle is time.Mine is a project that will span several years, so there isn’t the instant gratification of having immediate results. It felt great to get funding for each delegate, but I’m really eager to see the projects come to fruition in the years to come—they’re going to be amazing!

Poets.org: Is there a poem on Poets.org that inspires you and your work in Alabama? How so?

AMJ: I may be a broken record, but that’s fine by me. I have to go to Lucille Clifton. She always leads me. I’m thinking, maybe the poem that fits best with my work in Alabama and beyond is “cutting greens.” Sure, greens—a common sight and delicacy in the Deep South. But, more than that, the idea of mixing greens—maybe turnip and collard—unlike each other, but still greens, all the same. Just like us. We are not the same. We are strange to each other, but we can still find home in the bed pot, in the speaker’s Black hand which cradles and cuts. We are bonded, as the poem tells us, and that’s what I hope to do in Alabama. In America. To name our unique existences and show that they all matter in the pot of boiling greens. We are not melting in that pot—we are still whole, but we do need each other to make a meal. We are necessary to each other. We must know each other and make room as we curl around each other in this life; as we face the knife, which may cut me first, but is coming for you, too; as we understand our global kinship and the ambrosial pot liquor; what we could be if we were our best loving selves on Earth.