Teach This Poem, though developed with a classroom in mind, can be easily adapted for remote learning, hybrid learning models, or in-person classes. Please see our suggestions for how to adapt this lesson for remote or blended learning. We have also noted suggestions when applicable and will continue to add to these suggestions online.

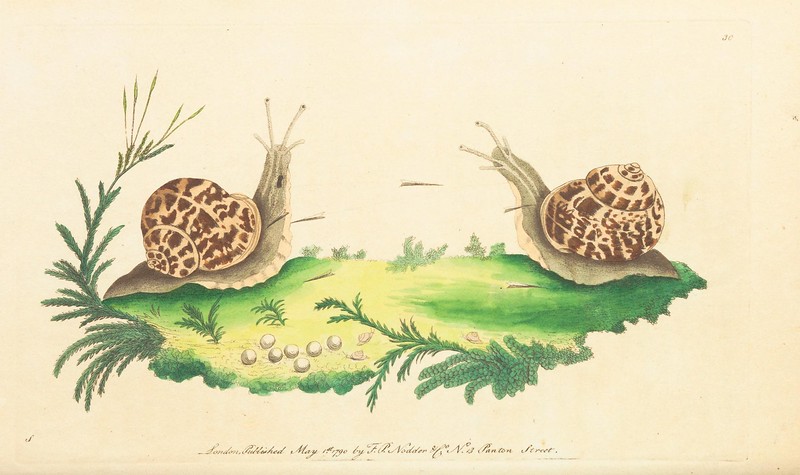

View this image of garden snails from 1789-1813.

The following activities and questions are designed to help your students use their noticing skills to move through the poem and develop their thinking about its meaning with confidence, using what they’ve noticed as evidence for their interpretations. Read more about the framework upon which these activities are based.

-

Warm-up: Look closely at the image of the snail. What do you notice about this animal? Look again. What else do you see? (Teachers, you could also encourage your students to browse the book this image came from here or gather pictures of all of the animals listed in the poem and ask students what these animals might have in common.)

-

Before Reading the Poem: Read the epigraph that accompanies the poem. Read this short article about invertebrates. Discuss with a partner or small group what might make invertebrates more at risk for extinction.

-

Reading the Poem: Read the poem “Characteristics of Life” by Camille T. Dungy silently. What do you notice about the poem? Annotate for any words or phrases that stand out to you or any questions you might have.

-

Listening to the Poem (enlist two volunteers to read the poem aloud): Listen as the poem is read aloud twice, and write down any additional words and phrases that stand out to you.

-

Small-group Discussion: Share what you noticed in the poem with a small group. Based on the details you just shared and your activities from the beginning of class, what can you tell about the speaker? What part of the speaker’s nature drives them? “What part of your nature drives you?” Why?

-

Whole-class Discussion: How does the epigraph relate to the poem? How might the poem be different without it? Why might the speaker feel the need to “speak for” these creatures? What is the impact of the title on the poem?

-

Extension for Grades 7-8: Imagine a conversation between two or more of the quieter creatures in the poem. For example, what might the damselfly say to the caterpillar? What might these animals discuss about extinction?

-

Extension for Grades 9-12: (Teachers, you may want to partner with a science teacher for this assignment.) In this article, the poet discusses how the poem speaks up for creatures: “To speak up for the life forms of the world in this sort of radically empathetic way is, as you suggest, a kind of witness. It’s also a kind of activism. And it’s also a kind of love.” With this in mind, research more about biodiversity in your own community, city, or state. Create a poem that answers the question: “What part of your nature drives you?” What kinds of creatures might you want to “speak up for”?

The Treehouse Climate Action Poem Prize honors exceptional poems that help make real for readers the gravity of the vulnerable state of our environment.

Read the 2020 winning poems:

“Letter to My Great, Great Grandchild” by J.P. Grasser

“O” by Claire Wahmanholm

“My Eighteen-Month-Old Daughter Talks to the Rain as the Amazon Burns” by Dante Di Stefano

This week’s poetic term is epigraph, referring to a quotation set at the beginning of a literary work or one of its divisions to suggest its theme. Read more.